The Genesis of the District Survey Report

Environmental regulation of mining minor mineral in India did not emerge as a coherent framework, but reactively to regulatory gaps that became increasingly visible over time. Early Environmental Impact Assessment notifications were ill-equipped to capture the cumulative environmental consequences of dispersed and fragmented minor mineral extraction across riverine and non-riverine landscapes.

Recent decisions of the Supreme Court (here and here) have emphasised on the centrality of the District Survey Report (DSR) in regulating mining of minor minerals[1] and have reiterated that environmental clearance for sand mining cannot be granted unless the DSR contains scientifically valid studies on river replenishment capacity.

Against this backdrop, this article traces the evolution of the District Survey Report as a regulatory mechanism that represents a shift in the governance of mining of minor minerals, from fragmented, lease-centric clearance to a cumulative, district-level planning framework. By examining the development of the EIA regime, the decision of Deepak Kumar v. State of Haryana, (2012) 4 SCC 629, and the subsequent institutionalisation of DSRs through executive guidelines, the article demonstrates how environmental regulation of minor minerals has been fundamentally recalibrated with the advent of DSR.

The Early Environment Impact Assessment Regime:

The first Environment Impact Assessment Notification was issued on 27.01.1994 (“EIA 1994”), which required prior environmental clearance only for mining of major minerals where the mining lease area exceeded 5 hectares[2].

The EIA 1994 thus adopted an area-based approach to environmental clearance and limited scrutiny to leases for major minerals exceeding 5 ha. Mining of minor minerals such as sand, gravel, and clay was entirely excluded from its scope. While proceeding on the assumption that that mining on a small-scale (less than 5 ha) and mining of minor minerals posed no environmental risk, it completely failed to account for the cumulative nature of such mining.

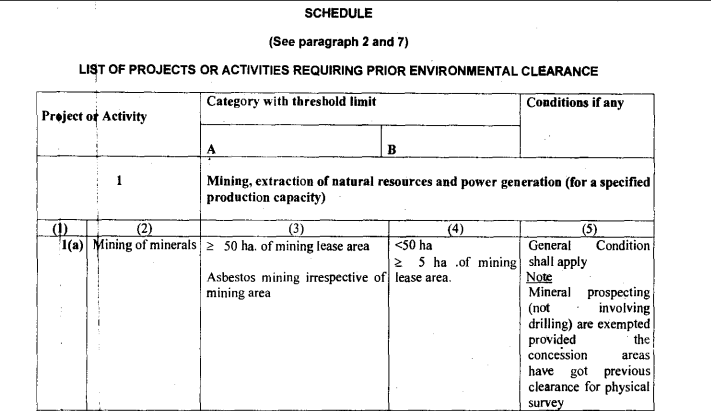

The MoEFC on 14.09.2006 issued a new EIA Notification (“EIA 2006”) bringing within its purview both major and minor minerals. The Schedule to the EIA 2006 read as under:[3]

The Schedule to the EIA dated 14.09.2006

However, despite this inclusion of minor minerals, the EIA 2006 retained the five-hectare threshold. Environmental clearance was required only where the mining lease area was five hectares or more, regardless of whether it involved mining of minor or major minerals.

This limitation was routinely exploited by State authorities through the deliberate fragmentation of mining areas into multiple sub-five-hectare leases. Although each lease appeared environmentally insignificant in isolation, their collective impact was devastating. Large-scale extraction proceeded for years without any prior environmental clearance, creating a regulatory blind spot that led to judicial intervention in Deepak Kumar v. State of Haryana, (2012) 4 SCC 629.

A Judicial turning point: Deepak Kumar v. State of Haryana (2012):[4]

In Deepak Kumar(supra), the core issue before the Hon’ble Supreme Court was whether auction notices for mining leases for minor minerals covering areas of less than 5 Ha. could be granted without prior environmental clearance under the EIA 2006 or without conducting a proper study of such mining on the environment.

The Supreme Court categorically rejected the assumption that extraction of minor minerals from small lease areas is environmentally benign. It recorded that there was no material before it to demonstrate that removal of sand, gravel, and boulders from the notified riverbeds would not result in environmental degradation or loss of biodiversity[5]. The Court also elaborated that extraction of alluvial material from within or near a riverbed directly alters the physical habitat characteristics of rivers, including bed elevation, substrate composition and stability, water depth, flow velocity, turbidity, sediment transport, discharge patterns, and temperature[6]

The Court held that issuing auction notices without conducting any study on the possible environmental impact of mining in riverbeds reflected a complete disregard for scientific assessment[7]. The Court emphasised that where extraction of alluvial material affects river stability, flood risk, biodiversity, and habitat integrity, it is no answer to claim that leases are small in size, because their collective and cumulative impact may be significant, necessitating a proper environmental assessment plan[8]

In addition to environmental clearance, the Supreme Court observed that States and Union Territories must subject minor mineral mining to a simplified but strict regulatory regime, carried out only under an approved mining plan. Such plans ought to address production levels, mechanisation, machinery used, fuel consumption, tree felling, environmental impact, and reclamation and rehabilitation of mined-out areas[9]

Giving operative force to its reasoning, the Supreme Court issued a clear and binding direction that all mining leases for minor minerals, including leases and renewals for areas of less than five hectares, shall be granted by States and Union Territories only after obtaining prior environmental clearance from the MOEFC [10]. This direction decisively closed the regulatory loophole that had existed under the EIA 1994 and EIA 2006 and put an end to the practice of lease fragmentation as a means of evading environmental scrutiny

Further, the decision in Deepak Kumar (supra) thus laid the jurisprudential foundation for a science-based, cumulative, and constitutionally anchored approach to regulating minor mineral mining

Conceptualizing Environment Impact Study: Birth of DSR (2016-2020)

A key outcome of the directions issued in Deepak Kumar (supra) was the conceptualisation of the District Survey Report (DSR) as a foundational planning and decision-making instrument.

In furtherance of these directions, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change first amended the EIA, 2006 by Notification S.O. 141(E) dated 15.01.2016[11] (“2016 Amendment”), formally introducing the requirement of preparation of a District Survey Report (“DSR”) for sand mining as a legal pre-condition for granting environmental clearances.

As per this notification, the main objective for the preparation of District Survey Report was to ensure Identification of areas of aggradations or deposition where mining can be allowed; and identification of areas of erosion and proximity to infrastructural structures and installations where mining should be prohibited and calculation of annual rate of replenishment and allowing time for replenishment after mining in that area.[12]

Further, Appendix X also prescribed the structure for preparation of District Survey Reports.

The Sand Mining Management Guidelines, 2016

The MoEFC issued the Sustainable Sand Mining Management Guidelines in March 2016 (“SSSMG”)[13], marking the first comprehensive policy framework specifically governing sand and other minor mineral mining.

The SSSMG explained that the preparation of the DSR is an important initial step[14] to give effect to the principle that river/ natural resources must be utilized for the benefit of the present and future generation, so river resources should be prudently managed and developed.

To operationalise this approach, the SSSMG provided detailed guidelines as to the structure of the District Survey Report[15]. This framework marked a clear shift towards long-term, science-based management of mineral resources, moving away from fragmented and short-term extraction practices.

Judicial reinforcement of the DSR regime

While the executive framework post-Deepak Kumar sought to institutionalise scientific planning through District Survey Reports, it was judicial intervention by the National Green Tribunal (NGT) that transformed the DSR from a policy guideline into a legally enforceable pre-condition for minor mineral mining.

The first significant judicial articulation of the binding nature of DSRs came from the NGT in Anjani Kumar v. State of U.P., 2017 SCC OnLine NGT 979. The Tribunal held that preparation of a DSR in accordance with Appendix X of the EIA Notification, 2006, is a condition precedent to the grant of any sand mining lease or environmental clearance[16]. It categorically rejected the State’s argument that departmental surveys conducted for auction or revenue purposes could substitute a District Survey Report[17]. By enforcing the the preparation of DSR as an initial step, and only thereafter granting mining leases, the Tribunal gave concrete legal effect to the principles laid down in Deepak Kumar (supra)

Thereafter, the Hon’ble High Court of Jharkhand In Court on its Own Motion v. State of Jharkhand (W.P. (PIL) No. 1806 of 2015), held that DSR was also mandatory in case of other minor minerals such as bajri.

Despite the formalisation of the DSR framework through the SSSMG and the subsequent strengthening of Appendix X in 2018, illegal sand mining continued unabated across several States. The Hon’ble National Green Tribunal repeatedly found that, DSRs were often prepared in a perfunctory manner, bearing little relation to site specific conditions, and that post clearance monitoring remained largely ineffective. In decisions such as Sudarsan Das v. State of West Bengal, Mushtakeem v. MoEF&CC, Jai Singh v. Union of India, and NGT Bar Association v. Union of India, the Hon’ble Tribunal documented widespread illegal extraction, enforcement failures, and institutional apathy, noting that the existing regulatory framework had failed to curb environmentally destructive mining. These findings culminated in repeated judicial directions to the MoEFC to revisit and strengthen the 2016 Framework. In this backdrop, the Enforcement & Monitoring Guidelines for Sand Mining, 2020 (“EMGSM”) were formulated.

Enforcement & Monitoring Guidelines for Sand Mining 2020:

The MoEFC issued the EMGSM on 27.01.2020[18] to address failures in regulating sand and riverbed mining. It was framed as supplemental to and prevailing over the SSSMG in case of conflict, the EMGSM focussed primarily on sand and other minor minerals extracted from river systems/ To achieve this, the EMGSM mandated river audits, replenishment studies, public disclosure of DSRs, use of drone and satellite surveillance, constitution of district-level enforcement task forces, and adoption of transparent online sand trading systems.

The robustness of this framework was tested in Pawan Kumar v. State of Bihar (2020), where the NGT subjected the State’s interim and final DSRs to close scrutiny. The Tribunal found the DSRs to be fundamentally flawed, particularly in their failure to conduct proper replenishment studies and assess river morphology. Rejecting the State’s attempt to proceed with e-auctions on the basis of defective DSRs, the NGT held that no mining lease for sand or other minor minerals can be granted in the absence of a valid, guideline-compliant DSR. The decision reaffirmed that the DSR is not an advisory document but the scientific foundation upon which environmental clearance must rest.

The matter reached the Supreme Court in State of Bihar v. Pawan Kumar, (2022) 2 SCC 348, where the Court affirmed the NGT’s reasoning in unequivocal terms. The Supreme Court held that preparation of a DSR in accordance with the EIA Notification, Appendix X, and applicable guidelines is a mandatory pre-condition for any auction, e-auction, or grant of mining lease for minor minerals. The Court rejected the notion that environmental compliance could be postponed to a later stage, reiterating the principle articulated in Deepak Kumar that environmental clearance must precede and not follow allocation of mining rights. In doing so, the Supreme Court firmly entrenched the DSR as a binding legal requirement rather than a discretionary administrative exercise.

Conclusion and way forward

The cumulative effect of these judicial and regulatory developments has been to fundamentally recalibrate India’s approach to sand and minor mineral mining. Taken together, these reforms have repositioned the DSR as a vital report, and a pre-requisite for mining of minor minerals. Courts have made it unequivocally clear that sand and other minor mineral mining can only be done after the preparation of this report and that the preparation of this report must precede and not follow allocation of mining rights.

The DSR now operates as a jurisdictional pre-condition: without a valid, scientifically grounded, and publicly vetted DSR, environmental clearance, auction, or grant of lease is legally unsustainable.

The next article will move from the formulation of DSR to examine the substantive requirements and preparation of District Survey Reports, including the scientific parameters, replenishment studies, and evolving judicial standards that determine their validity.

References

[1] Section 3(e) of the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957 (‘MMDRA’) defines minor minerals to include building stones, gravel, ordinary clay, ordinary sand other than sand used for prescribed purposes and any other mineral as declared by the Central Government

[2] Schedule I, EIA Notifcation, 1994 - “…20. Mining Projects *(major minerals)* with leases more than 5 hectares”

[3] https://environmentclearance.nic.in/writereaddata/EIA_Notifications/1_SO1533E_14092006.pdf

[4] Deepak Kumar v. State of Haryana, (2012) 4 SCC 629

[5] Para 8, Deepak Kumar v. State of Haryana, (2012) 4 SCC 629.

[6] Para 9, Deepak Kumar v. State of Haryana, (2012) 4 SCC 629

[7] Para 11, Deepak Kumar v. State of Haryana, (2012) 4 SCC 629

[8] Para 11, Deepak Kumar v. State of Haryana, (2012) 4 SCC 629

[9] Para 21, Deepak Kumar v. State of Haryana, (2012) 4 SCC 629

[10] Para 29, Deepak Kumar v. State of Haryana, (2012) 4 SCC 629

[11] https://environmentclearance.nic.in/writereaddata/EIA_Notifications/27_SO141E_15012016.pdf

[12] Appendix X, Notification S.O. 141(E) dated 15.01.2016

[13] SSSMG, 2016, https://www.jseiaa.in/uploads/notification/1719469544.pdf

[14] Page 21, SSSMG, 2016

[15] Page 24 – 27, SSSMG, 2016, https://www.jseiaa.in/uploads/notification/1719469544.pdf

[16] Para 65, Para 86, Anjani Kumar v. State of U.P., 2017 SCC OnLine NGT 979

[17] Para 94, Anjani Kumar v. State of U.P., 2017 SCC OnLine NGT 979

[18] EMGSM, https://environmentclearance.nic.in/writereaddata/SandMiningManagementGuidelines2020.pdf